So you’ve built an awesome game that the team is loving, and your user-testing is returning good results; now it’s time to release it to your players!

How do you explain this slice of awesome that is your game? We commonly use the terms First Time Use Experience (FTUE) or perhaps new user Onboarding to cover this aspect of product development. I will discuss both in detail. But it’s important to note that the experience is not the thing to explain to your user. A game is a set of systems that are layered around a core which your player interacts with and are experienced by your user. Full of the best intentions, teams will sometimes try to explain the full value the game offers, and that usually means explaining multiple systems and features to new players up front. This can overwhelm new players. A more scalable approach is to know how your game’s systems interconnect, and start with a level that is just the core. Then let the player build their own experience as the game unfolds before them over time and subsequent levels.

So how do you ensure players will understand the heart of your game? And more importantly, how do you ensure that they will stick around to discover the wonderful experience you have created? Let’s jump in!

2 Words – 2 Timelines

FTUE & Onboarding.

Many times these terms are used interchangeably across companies, or even within teams. I’d like to suggest they are separate and distinct when introducing new players to your game, or introducing existing users to a new game mode or feature on a live service game. I’ve seen the most success with intentionally using FTUE and Onboarding as follows – they can be thought of as two scopes of player learning.

- FTUE The first 60 seconds and the first 15 minutes of your game. By using kinesthetic learning, you are teaching the user how to navigate & interact with the game at a basic but enjoyable level. Your player learns by doing.

- Onboarding: the first seven days of a new game, or of a major update or expansion. You are giving your player new systems or ways to interact with your game that allow the player to form longer-term and more complicated inter-session goals.

When it comes to your FTUE, you are striving for simplicity and clarity of gameplay, so the first level(s) is always hand-crafted to introduce only core concepts. You must also weave a compelling narrative that immerses players from the very beginning. This starts in the first session, and oftentimes in the first minutes of gameplay. By starting the narrative early, players view the subsequent gameplay through the narrative’s lens and begin forming goals for the session. The power of emotion when a player is learning how to interact with your game cannot be understated. Once you have the “what” of your tutorial moments or level, make sure the team adds moments of excitement or surprise that fit your narrative or gameplay style.

Always allow your player to skip through, while still offering all the information as a self-contained sequence in a location like Settings.

Start the user off in a tailor-made level that teaches your basic gameplay concepts only. Leverage the power of emergent gameplay by layering in other UI or game systems only after your user is well versed in the core concept and has practiced it for several moves or even levels. In this way, your game’s depth and complexity is seen to emerge over time as the player progresses, learning new systems that add new UI as they go. In Super Mario Brothers, for example, the player started by running, jumping and stomping on enemies. Then the player is shown an enemy they could stomp on but behaves differently once stomped upon: it zoomed off, clearing out enemies as it went. This is a new way to use the jump/stomp the player had already been taught, that required no UI or explanation to a first time user, but added emerging complexity to the players decisions.

For your first time user in their first session, keep your user’s intent in mind when creating tutorial moments. Our brains respond differently to novel information, leading to better cognitive retention, this is a powerful tool in your design toolbox. Studies show that opt-in guides to gameplay concepts, where the user initiates the request for more information; or infrequent and seemingly irregular moments where the player is shown the gameplay concept, are better remembered and retained than a regular and therefore predictable sequence of explanations. Said another way, if a user feels they are being intentionally guided by predictable UI they will actually retain less of the information shown to them than if they feel they are finding/discovering how to play themselves and at their own pace.

From an Onboarding perspective, lean on emergent gameplay where UI and systems that are not needed for the first 15 minutes are intentionally hidden. If the player doesn’t need to know about it to enjoy moment-to-moment gameplay, introduce it in a later session.

When your player ends the first level or their first session, ensure the reason to return tomorrow is one of value to the player based on their prior gameplay and what they understand the game’s goals to be about. A very straight-forward option is for the player to receive a reward for an action they have just taken. However, a better option is to tie a future event into your narrative and give the player a narrative-based reason to come back tomorrow. And when integrating narrative into your user’s onboarding, triple check that your onboarding follows and explains the core narrative and loop as the team will have spent an amazing amount of time and effort on the immersive experience of the larger game.

A final component of onboarding design is for the team to agree on both the session length, and session goals for your first N sessions, and write these down. This may sound obvious but i’m surprised how many teams don’t explicitly state their design intent, instead seeking to track users by more generalized metrics or KPIs of engagement or retention. That said, what you write down may not bear out in your players usage as you observe it during a soft launch or longitudinal user study, but it’s better to have a specific hypothesis going in. This will help focus the team’s discussions of what to change, add or remove if users aren’t engaging or retaining in the way you’d expected.

A New Game v Live Service Update

Different approaches are required when building a new game versus when releasing a major expansion to an existing game, or a set of new features. When building a new game, you should not try to build your FTUE until late in development when the level of change in your features and maybe even some changes to your core loop are starting to settle down. Then you can assess them as a whole and observe where the heart of your game lies. When building something new, you won’t know how best to build introductory levels or content for your players until the mid-game is feeling really good. Once you have the mid-game set, then peel back the layers of the gameplay onion until you have the most common aspects of gameplay, which you introduce in a hand-crafted first level(s).

Conversely, when building an expansion or major release for a live service, you will be focused on showing the player how the new aspect of gameplay seamlessly integrates into their regular gameplay patterns. In this type of development you should think about both the FTUE and new user Onboarding throughout the development cycle. Unlike first launch, with a live service you have established metrics and established player behavior you can utilize. Intentionally designed gameplay which introduces the player to the new feature is still a best practice.Successful features may need a single “FTUE Moment” where the user is stopped during gameplay by explanatory UI, but generally the team should be able to utilize more of an onboarding approach (allowing the user to discover the feature’s depth over multiple sessions). If you find yourself needing to rely on multiple FTUE style features like repeated explanation or tutorial UI, examine the interconnectedness of the feature to your core loop. There may be a mis-match or disconnect in user goals and your feature’s capabilities.

Finally, regardless of whether you’re building a new game or a major expansion, while we all know that when we launch a game it is not totally perfect, the first two sessions do have to be perfect. Yes this means tuning things as well as you can, but it also means they are 100% bug free. This is key. It may be obvious to say no bugs, but remember: when your players don’t know your game, they don’t know what’s a bug and what’s seemingly bad design that confuses them. Therefore bugs impact your player disproportionately in the first session of using your product or playing your game, and zero bugs is easier to achieve than perfect tuning.

An Exercise in Explanations

Going through the exercise of explaining your moment to moment gameplay to new users can be useful for the team, it can show you systems that are not supporting your core user needs.

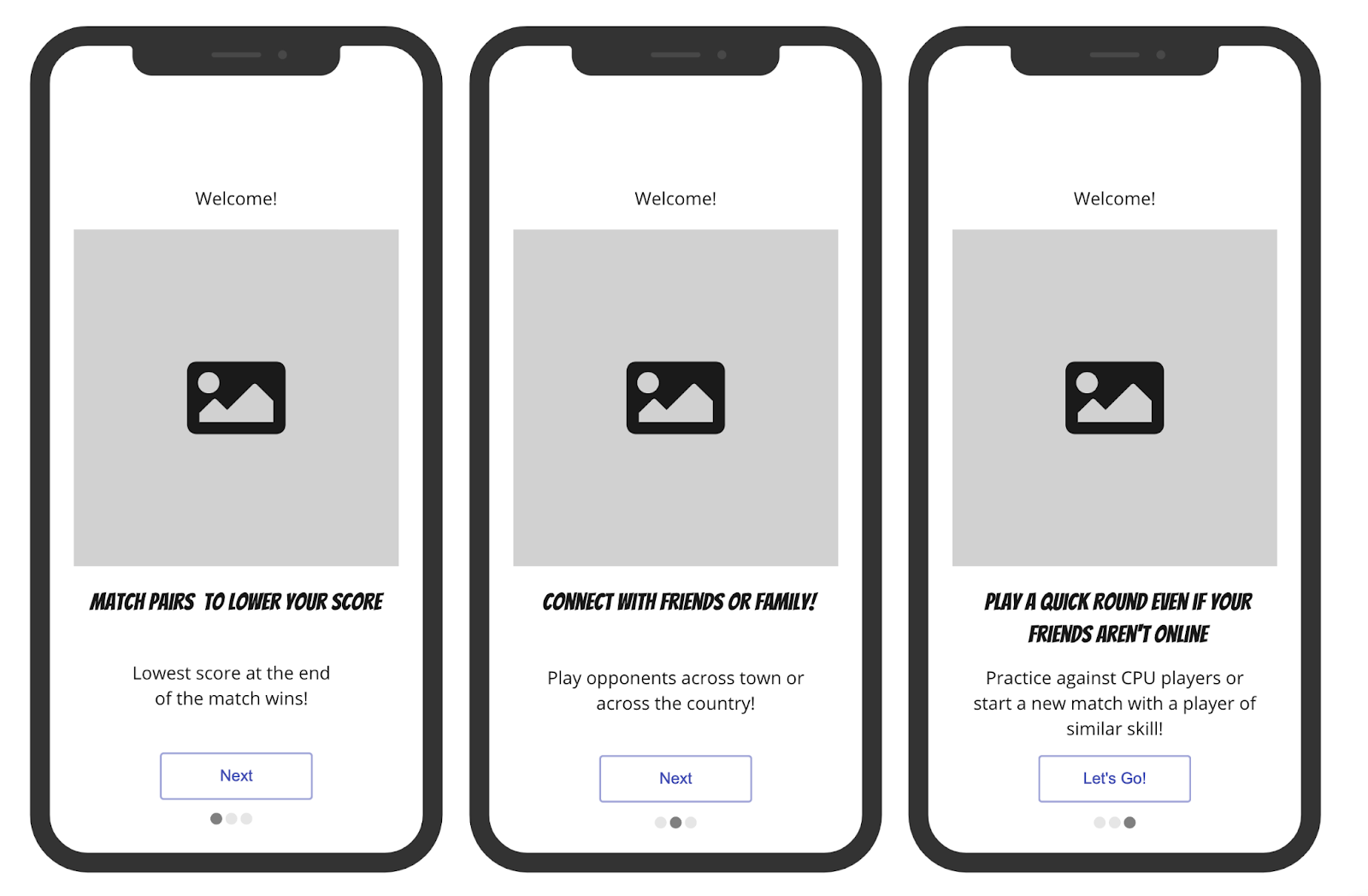

A simple exercise is to sketch out how you would explain your game in 3 to 5 notecards to a new user. Yes you can think of this as designing a FTUE UI, but the act of doing this in low fidelity wireframe can also give the team an opportunity to examine those ideas into gameplay or other UI moments. Who knows, you may need less of these ‘notecards” in your UI when you release, and less is more.

Can users explain to you in two sentences what your game is about after playing the first level? The first 1 or 5 or 15 minutes of the game? Asking this to new users who have never seen your game as much as possible once core gameplay & UI are solidifying can provide a good sounding board for the team.

In Conclusion

Two words, two timelines, two scopes. First time users need to be taught the basics of how to interact with your game in the first minute(s) of gameplay, and their own personal experience will be enhanced by starting an engaging narrative out of the gate. Then onboard them starting in the second session and over subsequent sessions to higher level gameplay concepts that build upon the core interaction shown to them in their first-time gameplay. By intentionally thinking of showing new users the beauty and wonder of your game over time, you are far less likely to overload them with too many or too large of concepts and drive them away from your game before they ever really start.