The value of User Experience Design to your team

Here’s our primer on the role User Experience Design can play in focusing your team on your players needs, designed to be lightweight and used when making top 10 games from Maxis to Zynga.

Where UX Fits

Historically, in the games industry, what we now call “user experience” (or “UX” for short) was usually the responsibility of the game designer, while user interface (or “UI”) design generally belonged to a visual artist in the art team. This often proved unsatisfactory, however, for a variety of reasons including inappropriate skillset (such as a game designer who was really a numbers expert but didn’t much understand user psychology) or confusion of responsibility. Over time a more considered understanding of the different design needs has emerged, leading to user experience being treated as an essential component in its own right.

Over the past decade especially, the need for a small group of individuals or a single individual to focus on user centered design exclusively has led to the rise of UI and UX design roles within the games industry, sometimes squished together as “UI/UX”. However the most appropriate way to think of this field is as a set of roles gathered under the “product” domain, such as “product design”, “product management” and so forth. Under this domain are several common job titles such as: User Interface Design, User Experience Design, Information Architecture, HCI (Human Computer Interaction) and User Research.

But what does it actually mean to say “you should use User Experience design in your game development process” or “you should think of this in terms of product”, or similar questions? At Mobile Game Doctor, we see UX design as a product design discipline which connects game design, product management, engineering and UI design. UX design can bring a whole new level of clarity and focus to your product offering by focusing on the customer’s behaviors and experience with the product overtime, be that within a single session, across sessions, or more importantly, how they are on-boarded to the product.

The aim of this article is to explain how all those pieces fit together.

Defining UI Design

To talk about the value of UX design we should first define UI design, as UI is where most people start to understand UX. When anyone talks about the user interface in a game, they generally mean explicit information displayed on-screen, such as in a frame overlaying a game world, and sometimes the means of interacting with that information. So the role of a UI designer is to design both the communication of information from the game to the user, and to interact with that information (generally through a combination of visual and auditory elements). This interface is created with the hardware form factor and input methods (touch, controller, mouse, gaze, etc) in mind.

For example, suppose you’re playing a combat racing game. A meter can tell you how much gas your car has left, and how far you can go till it runs out. An inventory management page for your car can tell you what upgrades have been applied to the car, and how to swap them out. A warning might flash up when an opponent throws a missile at you, so you know to deploy countermeasures. All of these are examples of user interface, whether as passive meter, interactive management screen, or an alert demanding your attention.

All of these examples need a UI designer to create the overall interface as well as define the visual presentation of said interfaces and define all its states. The designer does so with an eye to consistency and legibility, by establishing a visual style for all interface elements, a visual hierarchy of information and a cohesive icon style. The user can then read the different interfaces as a cohesive overall system.

Defining UX Design

The term “user experience” is often used interchangeably with user interface, but this is usually a mistake. While there is overlap, they focus on different areas and often have different outputs. UX looks at the user’s goals, wants and needs and figures out how to ensure these needs and goals can be met by a user interface without overwhelming the user cognitively or visually.

If your game or application is not retaining, or your engagement numbers are down, you may not be supporting your customers goals. This is where UX Design can help. Typically this means deploying several UX-specific tools to establish what those goals are and how they can best be served including:

- Prototypical Personas

- Site Visits

- The User Journey as Low-Fidelity Wireflows

- High Fidelity Wireframes

- Click Prototypes

- Hallway User Testing

Prototypical Personas

Whether consciously or unconsciously, most game development starts with some sort of target user in mind. Casual games, for example, often start with some vague idea of a middle-aged female user who enjoys puzzles. Roguelikes, on the other hand, usually have a dedicated younger PC gamer in mind as a target. Sometimes the development team essentially targets themselves (i.e. do they like their own game?), other times they have someone quite different in mind.

Regardless, one of the issues we often see is a lack of work to explicitly identify the target user and what they do or do not value. Such a lack of definition harms the value of all user experience design from the outset, and so this is why UX designers often begin by trying to define the target user. Typically they use “prototypical personas” to do so.

A persona is a shorthand for a set of wants, needs and pain points with an existing product or situation in the form of a prototypical user. The persona will have a name, demographics, their day-to-day life, etc. all of which is meant to help the team visualize that person, thereby more easily remembering those specific wants and needs. Generally a team will have a couple different personas representing different customer segments.

Prototypical personas are made up by the team in absence of Qualitative or Quantitative user data, demographics etc. very early in the project. Making up your user will tend to create a stereotype, but it is far better to get all that info into one place where everyone can see what is (and isn’t) a goal or need for your game to support.

Site Visits/Field Study

When building a game, the team will decide how long a good session is, the role of audio in the game, the appropriate lighting level for scenes. All of this depends on where their intended user will be playing the game. At the table or on the bus, that’s two very different environments, with different distractions, sounds, and ability to focus uninterrupted.

UX Designers will often visit the user to understand the context in which people will be (or are) using your product or playing your game in. Referred to as a Field Study, this may include private homes, offices, public transit, public spaces, with friends, without friends, etc.

The details of these locations are documented and used by the team much the same way that Personas are: as a shorthand for a context within which your game will be played.

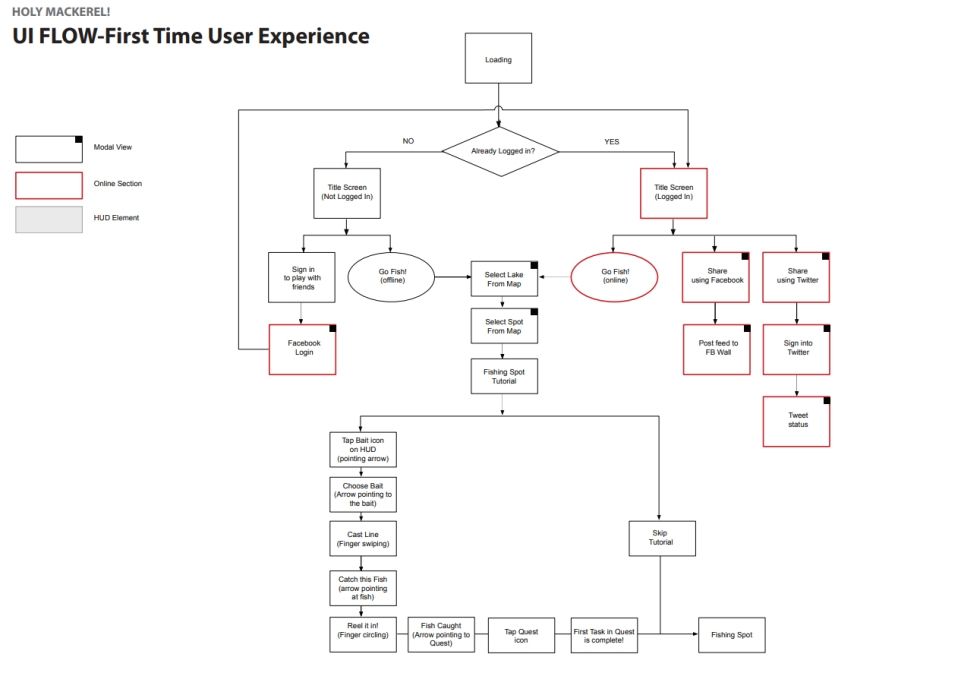

The User Journey in Low-Fidelity Wireflows

When a player plays through a game, their progression, from screen to screen, moment to moment is called player journey. If the team designs features individually, how well do they fit together as a whole? Sketching this journey out needs to be fast and easy.

UX uses the framework of the User Journey to examine – screen by screen, decision point by decision point – if the UI is providing the necessary information and input for the User to do the things they want to do with that feature or screen to meet the gameplay or session goals that they have formed for themselves. When working in-person, the most common tools were a dry-erase board, some markers during a conversation between UX & game design. Forced to be remote, we now have a growing variety of digital tools to allow real-time collaboration and real-time discussion, the key is keeping the process light and fast so you can explore many different journeys, with varying needs and goals in very simple low-fidelity wireframe format. This user journey in a screen-to-screen wireframe format is called a Wireflow.

High-fidelity wireframes

Once low-fi wireflows are created and the user journey agreed upon, each screen of the game will need to be detailed out in correctly sized User Interface elements. The goal is to ensure that all the needed UI inputs and informational elements can be fit on the screen and can be laid out in a logical and usable manner. Simplified, grayscale versions of UI elements are used to create sizing-accurate screen mockups.

There may still be visual and informational hierarchy issues when these wireframe screens are translated into high-fidelity UI mockups, but the needed revisions will be more contained, and the UX Designer can focus more on pure information architecture and information flow and ensure users’ goals and needs are being met in grayscale.

Click Prototypes

High-fidelity Wireframes can be quickly translated into a form that can be interacted with, or “clicked through” which allows the designer to see how their layouts for each screen read when connected together or jumped between. Modern wireframing software supports multiple input models and a variety of simple animations such as sliding, scaling and fading as well as sliding overlays and scroll views.

The resulting prototype may not have the subtlety of movement of an in-engine prototype, but can be made in a fraction of the time while leaving the engineer free to do other prototyping or exploration which requires the game engine, live data etc.

Prototypes are critical to ensuring great usability and that the product/feature will resonate with the target audience.

Hallway (Qualitative) User Testing

As teams work on a game and add layered systems and features, they develop blind spots to missing or unfinished features. That blue button in the corner that used to go to the character equipment screen, which now goes to the map? Does its location, the iconography, when it appears and disappears all make sense to a user who is new to the UI? How can you quickly check your game’s UI and flow?

Formal qualitative user testing is done by a trained researcher in a very controlled environment and uses participants specifically recruited because they fit the team’s target customer. UX Designers may have the capability to run very informal or “hallway” user tests using internal employees who are not part of the team and do not know the feature or game being developed.

There is certainly the likelihood of bias creeping into these informal hallway testing sessions as both the UX Designer and any team-members who help administer the test are not trained user researchers, but this type of test can be run regularly and quickly, and provides a very lightweight method to surface very obvious usability issues that the UX Designer or team may simply not see due to their familiarity with the game. The result is a much better games sent to the official qualitative user test run by your user researcher

How can you benefit from User Experience Design?

In summary, there are many tools and methods a dedicated UX designer can employ throughout the development process, from prototyping to pre-production, to production and as a live service. Get UX involved early to help a team focus better and move more nimbly!

- Users not retaining at the level you expected? Engagement dropping off? Not hitting your KPIs? UX can help with that.

- Are your customers and their voices missing from your process? UX can help with that.

- Is your prototype team working hard and delivering builds, but player comprehension is not improving? UX can help with that.

- Is your team having a hard time figuring out what features to prioritize and how to roadmap the rest out? UX can help with that.

- Are the bagels in your town too bready and not chewy enough? Ok, UX can’t help with that, but that’s about it.

Quick Links

Services

Join Our Newsletter

We will get back to you as soon as possible.

Please try again later.

All Rights Reserved | Mobile Game Doctor | Accessibility | Privacy Policy | Terms & Conditions